11

The Coen Brothers Essay: Style, Humor, and Darkness in Their Films

When you think of the Coen Brothers, you don’t just think of directors. You think of a world where a hitman sings along to Wicked Game while cleaning up a crime scene, where a man gets trapped in a woodchipper, and where a bumbling lawyer accidentally starts a war over a briefcase full of money. Their films aren’t just stories-they’re carefully constructed oddities, stitched together with deadpan humor, brutal violence, and a strange kind of moral quietness.

What Makes Coen Brothers’ Style Unique?

The Coen Brothers don’t follow Hollywood’s rulebook. They don’t chase trends. Their films feel like they were made in a room full of old books, vinyl records, and typewriters, with a TV playing a 1970s police drama in the corner. Their visual style is deliberate: wide-angle lenses, symmetrical framing, and long, quiet takes that let the tension build without music. You notice how they use space. In No Country for Old Men, the desert isn’t just a setting-it’s a character. Empty. Unforgiving. Silent except for the wind and the occasional click of a gun.

They rarely use close-ups unless it’s for a punchline. Think of Anton Chigurh in No Country-his face stays mostly in profile, his eyes cold and distant. Or Jerry Lundegaard in Fargo, sweating under a fluorescent light, his whole body shaking as he lies to a cop. The camera doesn’t rush to catch his reaction. It lingers. That’s their style: patience as a tool.

They also avoid traditional hero arcs. Their protagonists are often flawed, clueless, or just unlucky. There’s no grand redemption in A Serious Man. No triumph in Burn After Reading. Just chaos, miscommunication, and a universe that doesn’t care.

The Humor: Why It’s So Unsettling

The Coen Brothers’ humor isn’t jokes. It’s absurdity wrapped in realism. In The Big Lebowski, a man in a bathrobe gets dragged into a kidnapping plot because someone confused him with a millionaire. The plot makes no sense. And that’s the point. The humor comes from how seriously everyone takes the nonsense. Walter, the Vietnam vet, treats the situation like a military operation. The Dude just wants his rug back.

It’s not laugh-out-loud funny. It’s the kind of humor that makes you pause, then chuckle because you realize how true it is. People really do overreact to small things. They really do cling to rituals-like the Dude’s White Russian, or the German nihilists in The Big Lebowski who speak in perfect, chilling sentences about meaninglessness.

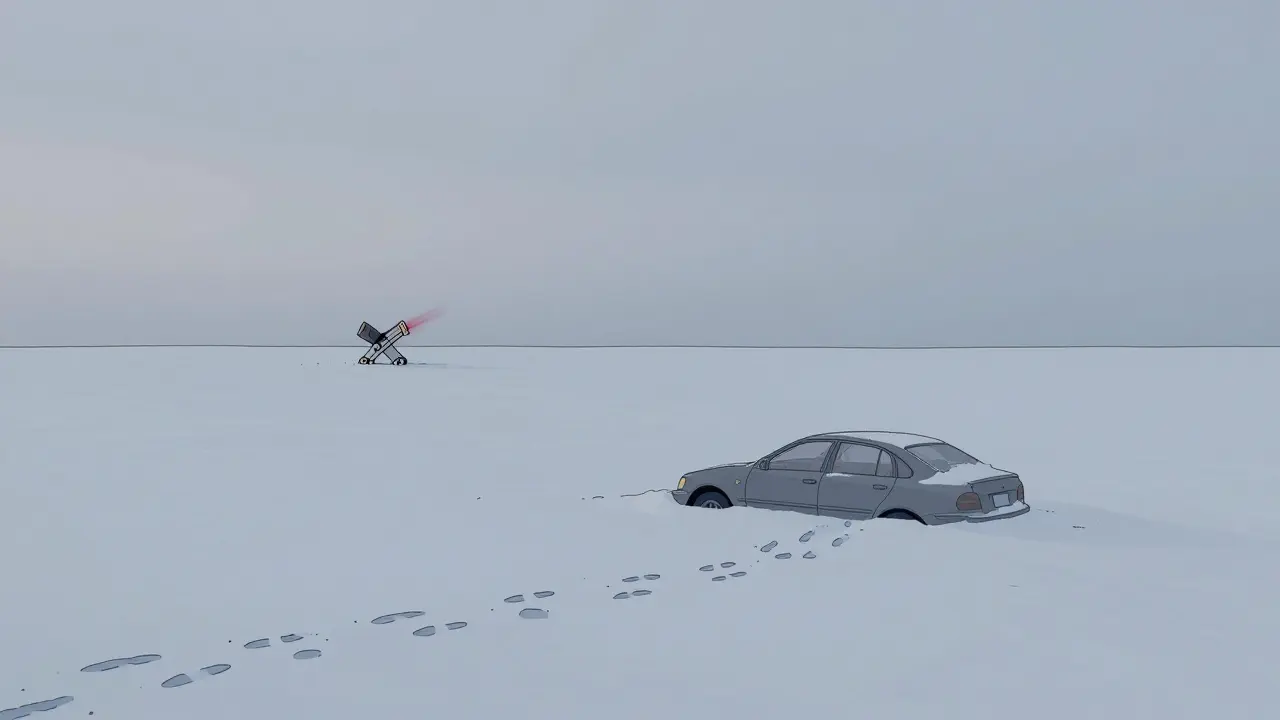

Even in their darkest films, there’s a dry wit. In Fargo, a man is murdered in a snowbank. Then, 15 minutes later, a cop eats a donut and says, “I’m not saying it’s funny, but…” That’s the Coen tone: violence and banality side by side. You don’t know whether to laugh or cry. So you do both.

The Darkness: Where Morality Goes to Die

The Coen Brothers don’t believe in karma. They don’t believe in justice. In No Country for Old Men, the villain wins. Not because he’s smart. Not because he’s lucky. He wins because the world doesn’t care who’s right. Sheriff Bell spends the whole movie trying to make sense of it all, and by the end, he just quits. He says, “I don’t think you can stop it.”

That’s their core theme: human effort is often meaningless. In Barton Fink, a writer tries to create art in a crumbling hotel, only to be crushed by forces he can’t understand. In A Serious Man, a man prays for answers-and gets silence. The Coens don’t offer hope. They offer observation.

And yet, there’s a strange beauty in that darkness. Their characters keep trying. They make bad decisions. They get angry. They cry. They smoke. They drink. They keep going. That’s what makes them human. The Coens don’t judge them. They just film them.

Music, Sound, and Silence

Music in Coen films isn’t background. It’s narrative. In O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the soundtrack isn’t just folk music-it’s the soul of the story. The Soggy Bottom Boys sing about being “in the middle of the river,” and suddenly, the whole journey makes sense. In Inside Llewyn Davis, every song feels like a confession. Llewyn sings, and you feel his loneliness in every note.

They also know when not to use music. The silence in No Country for Old Men is terrifying. No score. Just footsteps, wind, and the occasional sound of a coin flipping. That silence is louder than any orchestra.

Why Their Films Last

Most directors make movies that feel like products. The Coens make movies that feel like artifacts. You don’t watch them once and forget. You come back. Because each time, you notice something new. A detail in the set. A line you missed. A look that says more than the whole script.

They’ve made 18 feature films since 1984. Not one feels like a repeat. Each one has its own rhythm, its own rules. Miller’s Crossing is a gangster film with Shakespearean dialogue. True Grit is a Western told through the eyes of a 14-year-old girl. Inside Llewyn Davis is a tragedy wrapped in a folk song.

They don’t chase awards. They don’t care about box office numbers. They make films because they have to. And that’s why audiences keep watching. Because they know: when you sit down to a Coen Brothers movie, you’re not watching entertainment. You’re stepping into a world that doesn’t make sense-but somehow, feels more real than your own.

How They Work Together

Joel and Ethan Coen don’t have separate roles. Joel directs. Ethan writes. But it’s not that simple. They switch. They argue. They rewrite each other’s lines. Ethan once said, “We don’t really have a division of labor. We just do what needs to be done.”

That’s why their films feel so unified. No one person’s voice dominates. It’s a blend of Joel’s visual sense and Ethan’s love of language. Their partnership is the real secret weapon. They’ve never had a creative split. Not once. Even after 40 years.

Legacy: What They Changed

The Coen Brothers didn’t invent dark humor. But they perfected it. They proved that indie films could be both wildly original and wildly popular. They showed that audiences would sit through 120 minutes of silence, absurdity, and violence-if it was done with care.

They influenced a generation of filmmakers. Think of Barry on HBO. Or Sharp Objects. Even Stranger Things owes something to their tone. You can see it in the way characters react to chaos: with a shrug, a sigh, or a quiet, “Well, here we go.”

They didn’t change Hollywood. They changed what Hollywood could be. And they did it without ever saying, “This is important.”

What makes Coen Brothers’ films different from other directors?

The Coen Brothers blend deadpan humor with brutal realism in a way few others do. Their characters aren’t heroes or villains-they’re ordinary people caught in absurd, often violent situations. They avoid traditional storytelling arcs, rarely reward moral behavior, and use silence and music as narrative tools. Their visual style-symmetrical shots, wide lenses, and long takes-creates a detached, almost documentary-like feel that makes their worlds feel strangely real.

Are Coen Brothers films always dark?

Not always, but darkness is their signature. Even their funniest films, like The Big Lebowski, have moments of existential dread. In Fargo, a child is killed. In No Country for Old Men, the villain wins. Their humor often comes from the contrast between the mundane and the horrific. So while not every scene is grim, their worldview leans toward the bleak-without ever feeling nihilistic.

Which Coen Brothers film should I watch first?

If you want humor and heart, start with The Big Lebowski. It’s accessible, weird, and deeply human. If you prefer tension and atmosphere, go with Fargo. It’s tightly written, grounded, and still one of their most popular films. For something darker and more philosophical, try No Country for Old Men. It’s not for everyone-but it’s unforgettable.

Do the Coen Brothers use CGI in their films?

Rarely. They prefer practical effects, real locations, and in-camera tricks. In Fargo, the woodchipper scene used a real woodchipper. In The Big Lebowski, the bowling alley was a real alley with real bowlers. Even in True Grit, they used real horses and natural lighting. Their visual style is rooted in authenticity, not digital enhancement.

Why do Coen Brothers films have so much regional dialect?

They write characters based on real people they’ve met or read about. Ethan Coen has said they research dialects obsessively-listening to recordings, talking to locals, even hiring dialect coaches. In Fargo, they captured the Minnesota accent so accurately that locals still quote it. In O Brother, Where Art Thou?, the Southern drawl and folk idioms were painstakingly recreated. It’s not for flavor-it’s for truth.