3

The Power of Dialogue in Drama: How Aaron Sorkin and Quentin Tarantino Redefined Screenwriting

Most people think great drama is about big moments-explosions, betrayals, last-minute rescues. But the real magic often happens in the quiet spaces between those moments, in the words characters choose-or refuse-to say. Look at any scene from dialogue in drama that sticks with you, and you’ll find it’s not the action that lingers. It’s the rhythm. The silence. The way someone says, "I’m fine," when they’re anything but.

Dialogue Isn’t Just Words-It’s Character

Aaron Sorkin doesn’t write conversations. He writes battles disguised as chats. In The West Wing, characters don’t just talk about policy-they fight over it, dance around it, and sometimes collapse under its weight. His dialogue moves fast, stacked with overlapping lines, intellectual sparring, and moral urgency. It’s not realistic. It’s theatrical. And that’s the point.

Sorkin’s characters speak like they’re running a marathon while reciting poetry. They don’t pause for breath because they’re too busy trying to win the argument, prove their worth, or outrun their own doubts. In A Few Good Men, the courtroom climax isn’t about evidence-it’s about a single line: "You can’t handle the truth!" That moment works because everything before it built to that rupture in language.

Compare that to Quentin Tarantino. Where Sorkin’s people talk to change minds, Tarantino’s talk to fill space. His characters ramble about McDonald’s burgers, foot massages, or the meaning of "pulp fiction"-not because they need to, but because they’re alive in that moment. In Pulp Fiction, Vincent and Jules don’t discuss their mission. They debate the European version of a Quarter Pounder. And somehow, that’s more terrifying than any gunfight.

Tarantino’s dialogue isn’t about advancing plot. It’s about revealing character through obsession, humor, and contradiction. His people talk like real humans do-digressing, repeating themselves, getting distracted. But every tangent has purpose. A monologue about Royale with Cheese isn’t just quirky. It tells you Jules sees the world through a moral lens he can’t quite name. He’s trying to make sense of violence by turning it into a story.

How Silence Speaks Louder Than Words

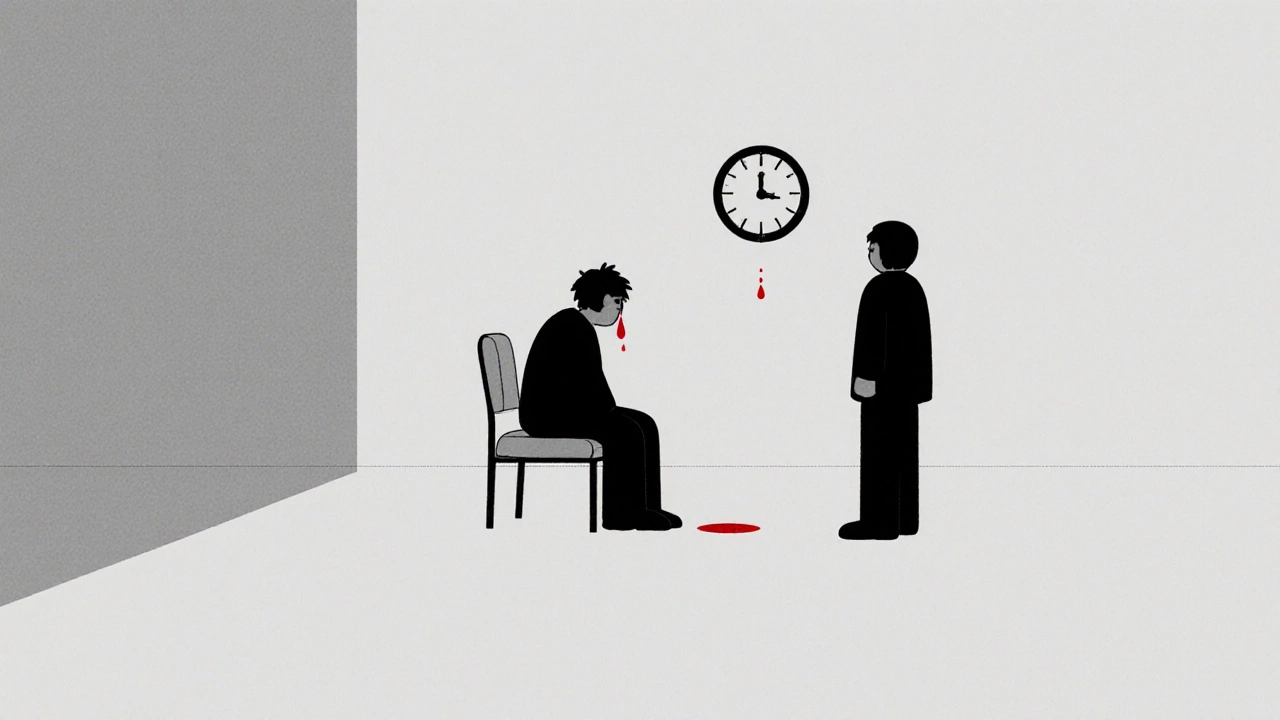

Both writers understand that what’s left unsaid is just as important as what’s spoken. In Sorkin’s The Social Network, Mark Zuckerberg sits across from Erica Albright after she breaks up with him. He doesn’t apologize. He doesn’t beg. He just stares. The silence stretches. The camera holds. And in that quiet, you feel everything he can’t say: shame, arrogance, loneliness.

Tarantino does this too. In Death Proof, Stuntman Mike sits in a diner, smiling at two women who have no idea he’s a killer. He talks about cars, women, and stunt work. The conversation is normal. Too normal. The tension doesn’t come from what he says-it comes from what he’s hiding. The audience knows. The characters don’t. That gap? That’s where fear lives.

Great dialogue doesn’t just tell you what’s happening. It makes you feel what’s not being said. A pause. A glance. A half-finished sentence. These are the tools that turn lines into moments.

Structure: Rhythm Over Realism

Real people don’t talk like Sorkin’s characters. They stutter. They interrupt poorly. They say "um" too much. But drama isn’t about realism. It’s about emotional truth.

Sorkin’s rhythm is like jazz-complex, syncopated, built on anticipation. He uses dialogue to create momentum. Every line is a beat. Every response is a counterpoint. In Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip, a single scene might have five characters talking at once, each with a different agenda. The audience doesn’t get lost because the structure is clean: conflict, escalation, resolution-all in under three minutes.

Tarantino’s rhythm is looser, more unpredictable. He lets scenes breathe. He lingers on awkward silences. He lets characters repeat themselves just to show how stuck they are. In Reservoir Dogs, the opening scene of the gang chatting in a diner lasts nearly ten minutes. No one’s planning a heist. No one’s revealing secrets. They’re just talking. And yet, you’re hooked. Why? Because you’re learning who they are through what they choose to talk about-and what they avoid.

Both writers use structure to manipulate time. Sorkin compresses it. Tarantino stretches it. But both know that dialogue controls pacing better than any cut or camera move.

Dialogue as Power

In Sorkin’s world, words are weapons. In Newsroom, Will McAvoy doesn’t just deliver a news anchor monologue-he dismantles a culture of complacency. The speech isn’t just informative. It’s a call to arms. And it works because every word is chosen for impact. He doesn’t just say what’s true-he says it in a way that forces you to listen.

Tarantino’s characters use words differently. They use them to assert dominance, to mask fear, to perform identity. In Jackie Brown, Ordell Robbie doesn’t need a gun to control a room. He just says, "I’m not gonna let you walk out of here." And the room freezes. Not because he’s threatening violence-but because he’s speaking with absolute certainty.

Power in dialogue isn’t about volume. It’s about control. Who speaks first? Who interrupts? Who lets the other person finish? These aren’t small choices. They’re character-defining.

Why These Two Writers Matter

Sorkin and Tarantino represent two poles of modern screenwriting. One is intellectual, fast, and driven by ideology. The other is visceral, slow, and driven by atmosphere. But they share something deeper: they treat dialogue as the engine of drama, not just decoration.

Most TV and film scripts use dialogue to explain plot. Sorkin and Tarantino use it to reveal soul.

If you want to write powerful drama, stop focusing on plot twists. Start listening to how people really talk-when they’re scared, when they’re angry, when they’re trying to hide something. Then, exaggerate it. Strip it down. Twist it. Make it sing.

Great dialogue doesn’t need fancy words. It needs honesty. It needs rhythm. It needs silence. And above all, it needs to sound like someone who’s alive.

What Makes Dialogue Stick?

Think about the lines you still quote years later. They’re rarely the most dramatic. They’re the ones that feel true.

- "I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse." - The Godfather

- "You’re gonna need a bigger boat." - Jaws

- "I am your father." - The Empire Strikes Back

These lines work because they’re simple, specific, and loaded with meaning. They don’t explain. They imply. They don’t describe. They define.

When you write dialogue, ask yourself: Does this line reveal who someone is-or just what they’re doing? If it’s the latter, rewrite it.

How to Write Dialogue Like a Pro

Here’s how to start:

- Listen to real conversations-not just the words, but the pauses, the tone shifts, the interruptions.

- Read your dialogue out loud. If it sounds like something a person would actually say, keep it. If it sounds like a script, trash it.

- Cut 30% of the words. Most dialogue is bloated with filler.

- Give each character a verbal fingerprint. One uses metaphors. Another repeats phrases. A third speaks in fragments.

- Let silence do the heavy lifting. Sometimes the best line is the one that never comes.

Don’t write what you think people should say. Write what they would say if they were real-and if the stakes were life or death.

Why is dialogue more important than action in drama?

Action shows what happens. Dialogue shows why it matters. A character can shoot someone, but it’s the line they say before or after that makes you care-or hate them. In drama, emotion lives in language, not explosions. A quiet confession hits harder than a car crash because it’s personal.

Can dialogue be too stylized?

Yes-if it distracts from the character. Sorkin’s rapid-fire style works because every character has a clear voice and purpose. If dialogue feels like a writer showing off instead of a person revealing themselves, it breaks immersion. The goal isn’t to sound clever. It’s to sound true.

How do you know if your dialogue is working?

Read it aloud with someone else. If you both stumble, it’s too long. If you laugh at the wrong moment, it’s forced. If the silence after a line feels heavy, you’ve got it right. Good dialogue doesn’t need explanation-it just lands.

Do I need to write like Sorkin or Tarantino to be good?

No. You need to write like yourself. But study them. Learn how they use rhythm, silence, and subtext. Then find your own voice. The best writers don’t copy-they absorb. They take what works and make it their own.

What’s the biggest mistake new writers make with dialogue?

They use it to explain the plot. Characters shouldn’t say things they already know just so the audience understands. That’s called exposition, and it kills tension. Instead, let the audience figure things out through tone, body language, and what’s left unsaid.