4

Kurosawa vs. Ozu: Comparing Two Pillars of Japanese Cinema

Kurosawa and Ozu didn’t just make movies-they shaped how the world sees Japan. One filmed with thunderous action and sweeping landscapes; the other sat quietly in a tatami room, watching tea steam rise. Both are giants of 20th-century cinema, yet their styles are as different as a samurai sword is from a folded kimono. If you’ve ever wondered why one feels like a storm and the other like a sigh, you’re not alone. Their films still live in film schools, in streaming queues, and in the quiet moments when someone sits down and lets a 60-year-old movie change how they see silence.

What Kurosawa Built: Motion as Meaning

Akira Kurosawa didn’t make films to calm the mind. He made them to shake it. His camera moved. His actors ran. His rain fell in sheets. In Rashomon (1950), four people tell the same story-and none of them are telling the truth. The camera circles them like a predator. In Seven Samurai (1954), 147 minutes of tension build to a 40-minute battle that still holds up against anything made today. Kurosawa’s films are about chaos, honor, and the cost of survival.

He borrowed from Westerns, Shakespeare, and noir, but never copied. He made Throne of Blood from Macbeth and turned it into something only Japan could produce: a forest of whispering trees, a warrior consumed by ambition, and a wind that never stops howling. His use of wide lenses, deep focus, and sudden cuts created a rhythm that felt urgent, alive. Even his quiet scenes crackled with tension. When a character sat still, you knew something was about to break.

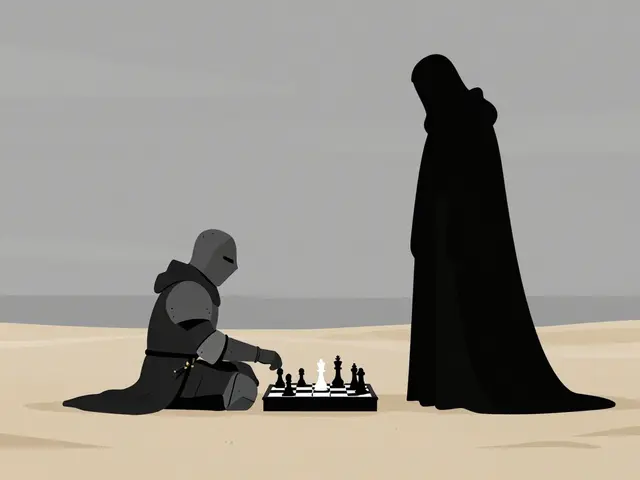

Kurosawa’s influence is everywhere. George Lucas stole the opening crawl from The Hidden Fortress. John Sturges copied Seven Samurai for The Magnificent Seven. Even today’s action directors use his framing-low angles, fast zooms, and characters moving in and out of the frame like pieces on a chessboard.

Ozu’s Quiet Revolution: Stillness as Story

Yasujirō Ozu didn’t move the camera. He didn’t need to. His films unfold like a slow breath. In Tokyo Story (1953), an elderly couple visits their grown children in the city. They’re treated politely, but not deeply. The children are busy. The grandchildren are loud. The parents sit quietly, sipping tea, staring out windows. No music swells. No dramatic music cues. No villain. No hero. Just life, as it happens.

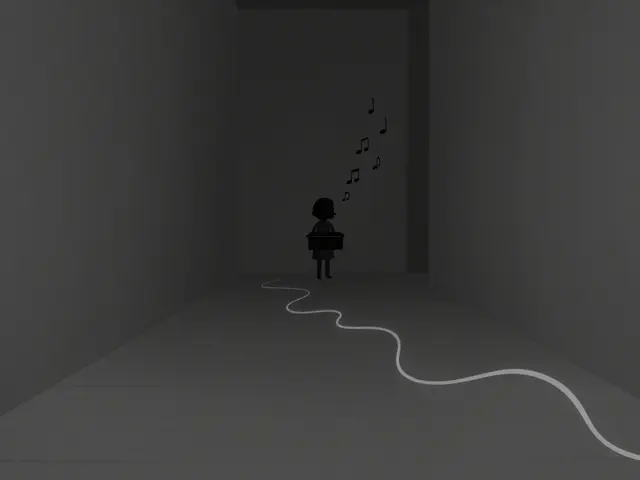

Ozu’s camera sat low-on the tatami floor, at eye level with someone seated. He called it the "pillow shot": a quiet moment between scenes-a kettle boiling, a empty hallway, a train passing outside. These weren’t filler. They were punctuation. They let the silence breathe. His films had no zooms, no pans, no tracking shots. Everything was still. And in that stillness, you felt everything.

His stories were about families falling apart, not because of betrayal, but because of distance. Time. Routine. The quiet erosion of connection. In Early Summer (1951), a daughter’s marriage isn’t a celebration-it’s a quiet surrender to expectation. The parents nod. They smile. They don’t say what they feel. That’s the heart of Ozu. Emotion isn’t shouted. It’s held.

He made over 50 films, almost all in the same style. Critics called him repetitive. They didn’t get it. He wasn’t telling different stories. He was circling the same one: how people stay close while growing apart. His films are the opposite of spectacle. They’re the opposite of noise. And that’s why they still hurt.

Style: Movement vs. Stillness

Compare the opening of Seven Samurai to the opening of Early Summer. Kurosawa’s film starts with dust clouds, horses galloping, men shouting. Ozu’s starts with a train arriving at a station. A woman steps off. She looks around. She walks home. That’s it.

Kurosawa’s compositions were dynamic. He used diagonal lines, deep space, and motion to create energy. His frames were packed. Every inch mattered. Ozu’s frames were empty. He left space. He framed faces in doorways. He cut to empty rooms. He let the silence speak louder than any line of dialogue.

Kurosawa edited for pace. He cut fast to keep you on edge. Ozu edited for rhythm. He held shots longer than most directors dared. He’d cut from a character speaking to a vase on a shelf. No transition. No fade. Just a shift in attention. It forced you to feel the gap between what was said and what was felt.

Kurosawa’s films had climaxes. Ozu’s didn’t. His endings were quiet. A character leaves. A door closes. The camera stays. The room empties. You’re left wondering if you missed something. Then you realize-you didn’t. The moment was the whole thing.

Themes: Honor vs. Home

Kurosawa’s heroes fought for ideals. They defended the weak. They stood against corruption. They died for principles. In Yojimbo, a ronin plays two gangs against each other-not for money, but because he can’t stand the cruelty. His morality is clear, even if his methods are brutal.

Ozu’s characters didn’t fight. They accepted. They endured. In Equinox Flower (1958), a father resists his daughter’s choice of husband. He doesn’t yell. He doesn’t threaten. He sits quietly. He drinks tea. He lets her go. His pain is real, but he doesn’t make it about himself. That’s the difference. Kurosawa’s men are warriors. Ozu’s men are fathers. One wins battles. The other loses slowly, without a fight.

Kurosawa’s Japan was a place of conflict-feudal, violent, uncertain. Ozu’s Japan was changing. Post-war. Urban. Quietly broken. His films show the collapse of tradition not with drama, but with the absence of it. The family shrine is empty. The kimono is packed away. The children don’t visit. The parents don’t complain.

Legacy: Who Changed Cinema More?

Kurosawa’s legacy is loud. He gave us the anti-hero, the lone wanderer, the epic battle. He proved non-Western stories could be universal. His films were the first Japanese movies to win international awards. He opened the door.

Ozu’s legacy is deeper. He showed that cinema didn’t need spectacle to move people. He proved that stillness could be powerful. That silence could be emotional. That family drama could be as gripping as a war. He influenced filmmakers like Wes Anderson, Abbas Kiarostami, and Hou Hsiao-hsien-not because they copied his style, but because they understood his truth.

Today, Kurosawa’s films are often shown in theaters with orchestral scores. Ozu’s films are watched in silence, late at night, alone. One is celebrated for its power. The other for its truth.

Which One Should You Watch First?

If you want to feel something big-adrenaline, rage, triumph-start with Seven Samurai. If you want to feel something small-loneliness, regret, quiet love-start with Tokyo Story.

Don’t pick based on reputation. Pick based on what you need. Kurosawa will make you want to stand up. Ozu will make you want to sit down and stay there.

Watch both. Watch them months apart. Let one settle. Then let the other break you open.

Are Kurosawa and Ozu the only important Japanese directors?

No. While Kurosawa and Ozu are the most globally recognized, other directors like Kenji Mizoguchi, Naruse Mikio, and Imamura Shohei made equally vital films. Mizoguchi focused on women’s struggles in feudal Japan, with long, flowing takes that mirrored the weight of tradition. Naruse captured the quiet despair of post-war urban life. Imamura explored the margins of society-prostitutes, criminals, the poor-with raw, unfiltered realism. But Kurosawa and Ozu remain the most studied because their styles are so distinct, and their influence so wide.

Why do Ozu’s films feel so slow?

They’re not slow-they’re deliberate. Ozu removed everything that distracted from emotion: fast cuts, dramatic music, camera movement. He wanted you to sit with the silence between words, the space between people. That stillness isn’t boredom. It’s intimacy. It’s the space where real feelings live. Most modern films rush past those moments. Ozu held them. That’s why his films still feel so honest.

Can you enjoy Kurosawa without liking action movies?

Absolutely. Kurosawa’s action scenes aren’t just spectacle-they’re moral tests. In Rashomon, the violence isn’t about who won. It’s about how people lie to protect themselves. In Throne of Blood, the battle isn’t about strategy-it’s about the collapse of a man’s soul. If you care about human psychology, power, guilt, or identity, his films are some of the deepest ever made. The action is just the surface.

Which director’s films are easier to understand for beginners?

Kurosawa’s films are often easier to follow because they have clear plots, strong heroes, and dramatic arcs. Seven Samurai or Rashomon give you a story you can grab onto. Ozu’s films require patience. They don’t have villains or big twists. You have to notice the small things-a glance, a pause, a tea cup left on a table. If you’re new to art cinema, start with Kurosawa. Then move to Ozu when you’re ready to sit with silence.

Do Kurosawa and Ozu ever appear in the same film?

No. They never collaborated. Their styles were too different. Kurosawa was loud, ambitious, and public-facing. Ozu was private, quiet, and avoided the spotlight. They worked in the same era, in the same country, but in separate worlds. Their films are like two sides of the same coin: one showing the world outside, the other showing the world inside.

Where to Start Watching

For Kurosawa: Begin with Rashomon (1950) for storytelling, then Seven Samurai (1954) for scale, and Throne of Blood (1957) for atmosphere.

For Ozu: Start with Tokyo Story (1953)-widely considered his masterpiece. Then watch Early Summer (1951) and Equinox Flower (1958) to see how his themes evolved.

All are available on Criterion Channel, MUBI, and Kanopy. No subtitles? Don’t worry. You’ll feel more than you understand.