6

Rashomon and the Unreliable Narrator: How Kurosawa Changed Cinema with Truth That Doesn't Add Up

Rashomon isn’t just a movie. It’s a mirror held up to how people remember, lie, and rewrite their own stories - even when they believe they’re telling the truth. Released in 1950, Akira Kurosawa’s film didn’t just win international awards. It rewrote the rules of storytelling in cinema by showing that truth isn’t a single thing. It’s a collection of conflicting versions, each shaped by ego, fear, and desire.

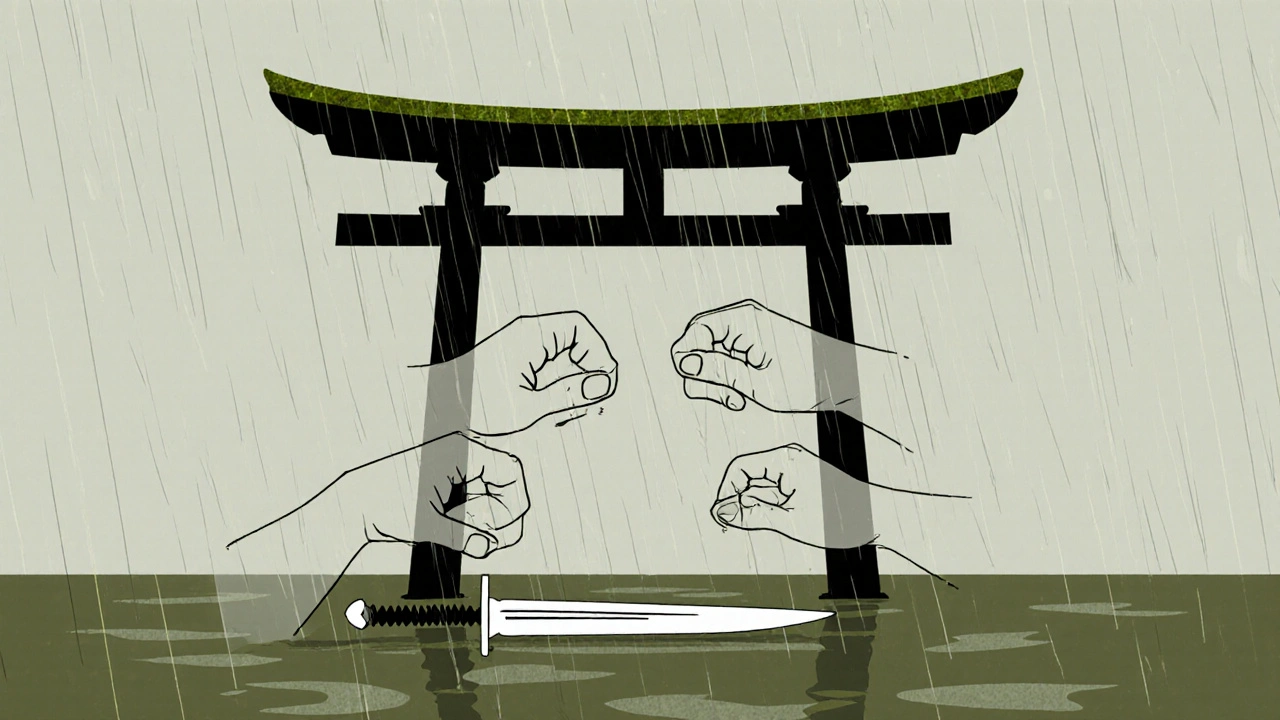

What Happens in Rashomon?

A samurai is dead. A woodcutter, a priest, and a commoner sit under the ruins of Rashomon Gate, recounting what they saw. But their stories don’t match. The bandit claims he killed the samurai in a fair duel. The wife says she was raped and begged her husband to kill her out of shame. The samurai, speaking through a medium, says he committed suicide out of honor. And the woodcutter? He saw something none of them admit: the cowardice, the cruelty, and the messy, ugly truth no one wants to own.

There’s no final answer. No voice of God. No cut to the real version. Kurosawa doesn’t give you the truth. He makes you feel how impossible it is to find.

The Unreliable Narrator Isn’t a Trick - It’s Human

Before Rashomon, unreliable narrators were mostly used in literature. Think of Poe’s narrators or unreliable first-person confessions in novels. But Kurosawa brought it to the screen in a way no one had done before. He didn’t just show one person lying. He showed four people, all convinced they’re telling the truth.

The bandit doesn’t lie to look heroic. He believes he was brave. The wife doesn’t lie to avoid blame - she genuinely remembers her husband’s look of disgust as the moment he chose shame over love. The samurai’s ghost doesn’t fabricate his death. He’s trapped in his own pride, rewriting his final moments to protect his identity.

This isn’t about deception. It’s about self-deception. Each narrator filters reality through their own wounds. The film asks: If everyone believes their version, who’s lying? And if no one is lying, then what is truth?

How Kurosawa Made It Feel Real

Kurosawa didn’t use fancy editing tricks. He didn’t flash back with different filters or voiceovers to signal a lie. He filmed all four versions the same way: with the same lighting, the same camera angles, the same actors. The only difference? The performances. The bandit’s swagger. The wife’s trembling voice. The samurai’s haughty tone. The woodcutter’s hesitant silence.

That’s what makes it unsettling. You can’t tell which version is fake because they all feel real. The sunlight through the trees. The rain on the leaves. The way the wind moves the grass. Everything stays the same. Only the people change. And that’s the point. The world doesn’t shift. The people inside it do.

There’s a moment in the film when the woodcutter, after hearing all the stories, says, “I saw it all.” But he didn’t tell the truth until the very end. Why? Because admitting he stole the dagger - the one thing everyone fought over - would make him just as guilty as the rest. He’s not a hero. He’s just another person who couldn’t face his own weakness.

Why This Still Matters Today

Look at social media. Look at courtrooms. Look at political debates. People don’t just lie. They reconstruct their past to fit the story they need to believe. A friend remembers an argument as you being cruel. You remember it as them being unreasonable. Both of you are telling the truth - as you experienced it.

Rashomon predicted this. Long before the internet gave everyone a platform to curate their version of events, Kurosawa showed how fragile memory is. How pride bends perception. How guilt reshapes history.

Modern films like Gone Girl, The Usual Suspects, and Shutter Island borrow from Rashomon. But none of them go as deep. They still want you to find the real version. Kurosawa refuses to let you. He leaves you in the rain, under the broken gate, wondering if truth even exists.

What Makes a Narrator Unreliable?

An unreliable narrator isn’t someone who lies on purpose. It’s someone whose perspective is broken. Maybe they’re traumatized. Maybe they’re proud. Maybe they’re afraid. In Rashomon, every narrator fits this. The bandit is a liar, but he’s also a man who needs to believe he’s a warrior. The wife is a victim, but she’s also someone who can’t live with the shame of being desired. The samurai is dead, but his ghost still clings to honor like a life raft.

Real people do this every day. A parent remembers their child’s first words as a miracle. The child remembers it as a cry for food. Both are true. Neither tells the whole story.

Kurosawa didn’t invent unreliable narration. But he proved it could work on film - not as a gimmick, but as a way to show how humans survive their own memories.

How Rashomon Changed Film

Before Rashomon, most films told stories like news reports: one version, one truth. The hero. The villain. The clear ending. Kurosawa shattered that. He showed that a single event can have as many truths as there are people who witnessed it.

That idea spread. European directors like Alain Resnais and Ingmar Bergman started playing with memory and time. American filmmakers like David Lynch and Christopher Nolan built entire careers on fractured narratives. Even TV shows like True Detective and Westworld owe something to Kurosawa’s quiet, rain-soaked gate.

But Rashomon didn’t just change storytelling. It changed how we watch. After seeing it, you start questioning every character. You wonder: Is this person lying? Or just protecting themselves?

The Last Scene: Hope in the Ruins

The film ends with the woodcutter taking in an abandoned baby. The commoner mocks him: “You’re no saint. You stole a dagger.” The woodcutter doesn’t answer. He just wraps the child in his coat and walks away.

That moment is the film’s quiet revolution. Truth might be broken. Memory might be twisted. But kindness? That’s real. You don’t need to know the full story to do the right thing. You don’t need to know who’s lying to offer help.

Kurosawa doesn’t give you truth. But he gives you something better: a reason to keep trying, even when you can’t be sure.

Why Rashomon Still Haunts Viewers

It’s not the violence. It’s not the setting. It’s the quiet horror of realizing you’ve done this too. You’ve told a story about yourself that made you look better. You’ve forgotten the part where you were wrong. You’ve convinced yourself you were the victim - even when you weren’t.

Rashomon doesn’t ask you to solve the mystery. It asks you to look inside. To ask: What version of myself am I telling right now? And why?