18

The Gaze Revisited: How Film Theory Evolved from Mulvey to Intersectional Critique

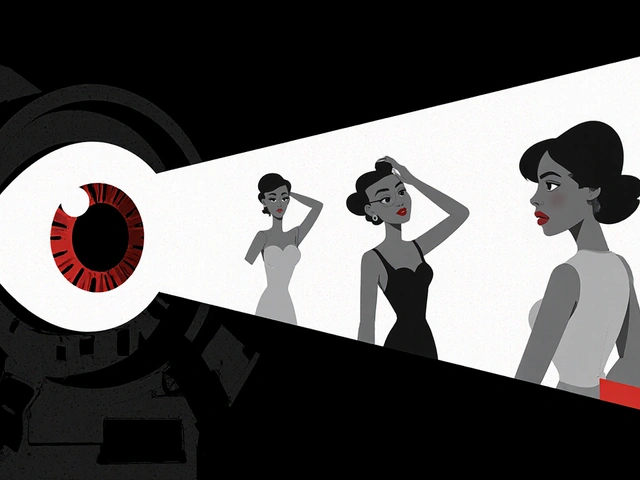

When Laura Mulvey introduced the concept of the male gaze in 1975, she didn’t just write an essay-she cracked open a window into how cinema had been silently shaping who gets to look, who gets to be seen, and who gets reduced to an object. Her paper, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, didn’t just analyze films. It exposed the machinery behind them: the camera as a male eye, the female body as decoration, the audience as complicit. Decades later, that gaze hasn’t disappeared. It’s just gotten more complicated.

What the Male Gaze Actually Did

Mulvey’s argument wasn’t abstract. She pointed to concrete patterns in classic Hollywood films. Think of the slow pan down a woman’s body in a 1950s noir, or the way a female character pauses to adjust her hair just so, as if aware she’s being watched. These weren’t accidents. They were coded behaviors-reinforced by editing, lighting, and camera angles-that turned women into objects of visual pleasure for a presumed male viewer. The camera didn’t just record; it participated. And the audience, whether they realized it or not, was trained to enjoy this dynamic.It wasn’t just about sex. It was about power. The male gaze structured narrative itself. Men drove the plot. Women existed to be looked at, desired, rescued, or punished. Even when women had agency, the camera often undercut it-zooming in on their lips as they spoke, lingering on their legs as they walked away. The gaze wasn’t neutral. It was a tool of control.

When the Gaze Got Messy

By the 1990s, scholars started asking: What about women who aren’t white? What about queer viewers? What about bodies that don’t fit the ideal? Mulvey’s model, groundbreaking as it was, assumed a universal female experience-one shaped by middle-class, heterosexual, white femininity. That version of womanhood didn’t represent most viewers.Black feminist theorists like bell hooks pushed back. In her essay Looking at Masters: The Oppositional Gaze, hooks argued that Black women watching films weren’t passive recipients of the male gaze. They watched differently. They saw themselves erased, mocked, or sexualized in ways white women weren’t. So they developed a counter-gaze: a critical, defiant way of watching that refused to accept the image on screen as truth. This wasn’t just resistance-it was survival.

Similarly, queer theorists like Judith Butler and Teresa de Lauretis showed that the gaze wasn’t just male or female-it was fluid. A lesbian viewer might not identify with the heterosexual objectification of women. A trans viewer might feel alienated by binary representations of gender. The gaze, they argued, isn’t fixed. It shifts depending on who’s doing the looking-and who’s being looked at.

Intersectionality Changes Everything

The term intersectional gaze didn’t come from one person. It emerged from decades of work by women of color, disabled filmmakers, LGBTQ+ critics, and postcolonial scholars. It’s not a single theory. It’s a framework for asking better questions:- Whose body is being fetishized-and why?

- Who gets to be the subject, and who remains the object?

- How do race, class, disability, and sexuality intersect to shape how a character is framed?

Take the 2018 film Black Panther. When Shuri, the brilliant young princess, appears in her lab, the camera doesn’t linger on her body. It lingers on her inventions. Her intelligence is the spectacle. This isn’t accidental. It’s a deliberate reversal of the colonial gaze that has historically reduced Black women to either hypersexualized stereotypes or invisible servants. Here, she’s the genius. The camera respects her mind.

Contrast that with early Hollywood’s portrayal of Asian women as the “Dragon Lady” or “Lotus Blossom”-two reductive tropes that combined exoticism with passivity. Even today, in some indie films, a Southeast Asian character might be framed in soft focus, bathed in warm light, as if her ethnicity is a mood, not a lived reality. The intersectional gaze asks: Who benefits from this framing? And who is silenced by it?

How Filmmakers Are Rewriting the Gaze

The shift isn’t just theoretical. It’s happening on set, in editing rooms, and in funding decisions.Director Ava DuVernay’s 13th doesn’t just show prison systems-it shows how the camera itself has been used to criminalize Black bodies for over a century. The film uses archival footage, but recontextualizes it. The gaze here is not passive. It’s accusatory. It turns the camera back on the viewer: How have you been complicit?

Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland treats its non-professional actors-not as symbols, but as people with histories. The camera doesn’t idealize poverty. It doesn’t romanticize. It observes. Long takes. Natural light. Minimal music. The gaze here is quiet, respectful, and deeply human.

Even streaming platforms are changing. Shows like Sex Education and Reservation Dogs don’t just include diverse characters-they center their perspectives. A queer teenager’s first kiss isn’t framed for shock value. A Native teen’s anger isn’t reduced to a stereotype. The camera doesn’t ask, Isn’t this interesting? It asks, What does this feel like?

Why This Matters Beyond the Screen

The gaze isn’t just about movies. It’s about how we see each other in real life. When media consistently frames certain bodies as objects-whether it’s women in ads, disabled people as inspirational tropes, or immigrants as threats-it trains us to think that way outside the theater too.That’s why film theory matters. It’s not about dissecting old films for fun. It’s about recognizing patterns that shape real power. When a brand uses a woman’s body to sell sneakers, it’s using the same logic Mulvey named 50 years ago. When a news clip zooms in on a Muslim woman’s headscarf while ignoring her words, it’s repeating the colonial gaze.

The intersectional gaze isn’t about banning certain images. It’s about demanding more complexity. It’s about asking: Who gets to tell this story? Who’s missing from the frame? And whose eyes are we really seeing through?

What to Watch Next

If you want to see the evolution of the gaze in action, try these films and series:- Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) - A lesbian romance where the gaze is mutual, not one-sided.

- Parasite (2019) - Class, not gender, becomes the dominant lens of observation.

- Transparent (2014-2019) - A trans father’s story told with depth, not spectacle.

- Minari (2020) - A Korean-American family’s life seen without exoticism or trauma porn.

- Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022) - Multiverse chaos, but the emotional core is a mother’s quiet, unglamorous love.

Each of these works refuses to let the viewer stay comfortable. They force you to ask: Who am I looking at? And why?

Can the Gaze Be Reclaimed?

Yes-but not by reversing the power. Not by making women look back at men the same way men looked at women. That’s just swapping roles, not changing the system.The real shift comes when the gaze becomes reciprocal. When a Black mother’s exhaustion is shown without pity. When a disabled dancer’s body is celebrated for its strength, not its deviation. When a queer teenager’s joy isn’t framed as a tragedy. That’s not representation. That’s recognition.

The gaze isn’t dead. But it’s no longer just one eye. It’s many. And the more we learn to see through them, the less power the old gaze has.

What is the male gaze in film theory?

The male gaze is a concept from feminist film theory, introduced by Laura Mulvey in 1975. It describes how cinema is structured to present women as objects of visual pleasure for a presumed male viewer. The camera, narrative, and editing often focus on women’s bodies in ways that serve male desire, reducing them to passive figures rather than active subjects.

How does the intersectional gaze differ from Mulvey’s male gaze?

While Mulvey’s male gaze focuses on gender and power dynamics between men and women, the intersectional gaze expands the analysis to include race, class, sexuality, disability, and colonial history. It recognizes that women aren’t a single group-Black women, queer women, disabled women, and Indigenous women experience visual representation differently. The intersectional gaze asks not just who is looking, but who is being looked at-and whose perspective is missing.

Is the male gaze still present in modern films?

Yes, but it’s less obvious. Modern films often mask the male gaze behind aesthetics-slow-motion shots of women in swimwear, close-ups on legs or lips, or framing that emphasizes physical appearance over character. Even in feminist narratives, the camera can still linger on bodies in ways that serve fantasy rather than truth. The difference is that audiences are now more aware, and filmmakers are increasingly challenged to justify those choices.

Can men be subject to the gaze too?

Yes-but differently. The male body is often objectified for spectacle or power, not vulnerability. Think of action heroes with chiseled abs or shirtless scenes framed as heroic. But this rarely carries the same weight as the female gaze: men aren’t typically reduced to their bodies as a form of control. The intersectional gaze also examines how masculinity is performed and punished on screen, especially for men of color or queer men.

Why does film theory matter in everyday life?

Film doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The way stories are told on screen shapes how we see people in real life. When media consistently frames certain groups as objects-women, people of color, disabled individuals-it reinforces stereotypes that affect hiring, relationships, and public policy. Learning to recognize the gaze helps us question what we’re being shown-and who benefits from it.