2

Horror Soundtracks That Scare: From The Exorcist to Hereditary

Some sounds don’t just play in the background-they crawl inside your skull and stay there.

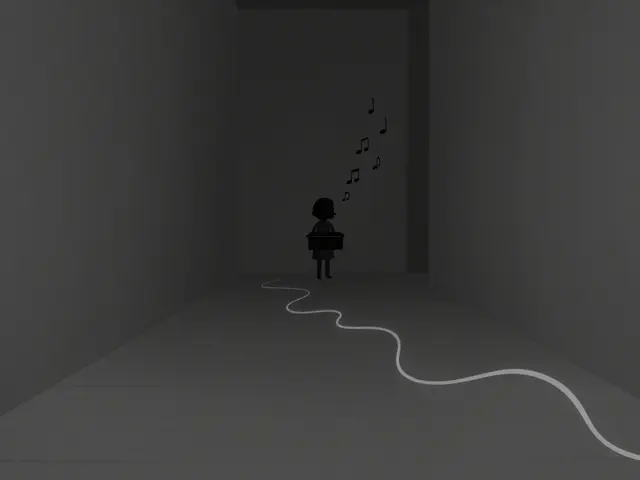

You’re watching a horror movie. The room is quiet. The character walks down a hallway. Nothing’s happening. Then-that sound. A low hum, barely there, like a refrigerator dying in another room. Your skin tightens. You didn’t see anything. You didn’t hear anything obvious. But your body already knows: something’s coming.

That’s the power of horror soundtracks. They don’t rely on jump scares. They don’t need loud crashes. They work in the silence, in the spaces between breaths. The best horror scores aren’t music you listen to-they’re sensations you feel.

From the 1973 chilling drone of The Exorcist to the eerie lullaby of Hereditary in 2018, horror soundtracks have evolved, but their goal hasn’t changed: to make you feel unsafe in your own skin.

What makes a horror soundtrack actually scary?

It’s not about notes. It’s about what those notes do to your nervous system.

Most music follows patterns-melodies, rhythms, harmonies. Your brain expects them. Horror soundtracks break those rules. They use dissonance: clashing tones that don’t resolve. They stretch silence until it feels like a trap. They drop bass frequencies so low you feel them in your chest before you hear them.

Studies from the University of London show that sounds below 20 Hz-inaudible to most people-still trigger fear responses in the amygdala. That’s why horror scores often use sub-bass tones. You don’t hear them. But your body reacts like you do.

Then there’s the use of non-musical sounds: breathing, creaking floorboards, distant whispers. These aren’t instruments. They’re psychological triggers. Your brain is wired to pay attention to human sounds, especially when they’re out of place. A child humming off-key? That’s scarier than a monster scream.

The Exorcist: The sound of possession

Before The Exorcist came out, horror movies used orchestral strings and sudden stings. William Friedkin wanted something else. He didn’t want music. He wanted a presence.

He hired Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells-a 30-minute instrumental piece originally meant for a solo piano and layered guitars. It was peaceful. Calm. Almost meditative. Friedkin flipped it. He slowed it down. Layered it with reversed audio. Added whispers. Turned beauty into something wrong.

The result? A theme that doesn’t scare you with loudness. It scares you with familiarity. You’ve heard that melody before-in a lullaby, in a music box. But now, it’s broken. It’s twisted. And it’s following the girl.

That’s the genius of it. The soundtrack doesn’t tell you something’s wrong. It makes you realize, slowly, that something always was.

Hereditary: The lullaby that never ends

Fast forward to 2018. Ari Aster’s Hereditary doesn’t use a traditional score. It uses silence, then shatters it.

Composer Colin Stetson built the soundtrack using only wind instruments-saxophones, bass clarinets-played with extreme techniques. He breathed through the instruments in ways that made them sound like dying animals. He recorded himself playing while wearing a mask, so his breaths were muffled, labored, like someone suffocating.

The most haunting moment? The lullaby. A child’s voice, singing a simple tune in a foreign language. It repeats. Over and over. In the background. During meals. In the hallway. You start to dread the next time it plays. You know it’s coming. And you can’t escape it.

That lullaby isn’t just a theme. It’s a curse. And the music doesn’t signal the horror-it *is* the horror.

Other soundtracks that rewrite fear

It’s not just these two. Horror has a rich library of sonic nightmares.

- Psycho (1960) - Bernard Herrmann’s violin screeches aren’t music. They’re the sound of a knife slashing through air. No drums. No bass. Just strings, sharpened to a point.

- The Shining (1980) - Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind used synthesizers to create drones that felt like the hotel itself was breathing. The music doesn’t build tension. It *is* the tension.

- It Follows (2014) - Disasterpeace’s synthwave score feels like a 1980s horror movie stuck in a loop. The beat never stops. It’s always behind you. Always coming.

- Get Out (2017) - Michael Abels mixed African tribal rhythms with classical strings. The result? A theme that sounds like a ritual you didn’t know you were part of.

Each of these scores works because they don’t treat horror like a genre. They treat it like a physical force.

How modern horror scores are changing

Today’s horror composers don’t just write music. They design experiences.

Tools like granular synthesis let them take a single whisper and stretch it into a 30-second drone. AI-assisted audio tools can generate random, unpredictable tones that mimic human anxiety. Some scores are now interactive-changing based on how long you stare at the screen or how fast your heart beats (yes, some theaters now use biometric sensors).

But the core hasn’t changed. The best horror soundtracks still use the same tricks from 50 years ago: silence, dissonance, repetition, and the human voice. Because the scariest thing isn’t the monster. It’s the sound that makes you think you’re alone… when you’re not.

Why we keep coming back to these sounds

Horror movies are about control. We watch them to feel fear in a safe space. But the soundtrack? That’s the one thing that can’t be controlled.

You can look away from the screen. You can cover your eyes. But you can’t cover your ears. And once that low hum starts, your body reacts before your mind catches up. That’s why these soundtracks stick with us. They don’t just scare us during the movie. They haunt us after.

You’ll be washing dishes. Or walking home. And suddenly-you hear it. A creak. A hum. A whisper. And for a second, you’re back in the theater. Or in your living room. Or in the hallway where you swore you heard breathing.

That’s the real horror. The music doesn’t end when the credits roll. It just gets quieter.

What makes a horror soundtrack different from other movie scores?

Horror soundtracks avoid traditional melodies and harmonies. Instead, they use dissonance, silence, low-frequency drones, and unnatural sounds-like reversed audio, distorted voices, or breathing-to trigger primal fear responses. They don’t tell you to be scared. They make your body react before your brain understands why.

Is it true that some horror sounds are below human hearing range?

Yes. Sounds below 20 Hz, called infrasound, are inaudible to most people. But research shows they can cause feelings of unease, dread, or even hallucinations. Composers like those behind The Exorcist and The Shining have used infrasound to create subconscious tension without the audience realizing why they feel off.

Why do horror movies use childlike lullabies?

Lullabies are tied to safety and comfort. When twisted-slowed down, sung off-key, or played in a foreign language-they become uncanny. The brain expects warmth, but hears something wrong. That dissonance between expectation and reality is deeply unsettling. Hereditary and The Ring both use this trick to make innocence feel threatening.

Can silence be scarier than music?

Absolutely. Silence forces your brain to fill the gap with imagined threats. Horror films like The Babadook and It Follows use long stretches of quiet to make every small sound-like a door closing or a footstep-feel dangerous. Your imagination becomes the monster.

What’s the most effective instrument in horror scores?

There’s no single winner, but the human voice is the most powerful. A whisper, a hum, a gasp-these are sounds we’re evolutionarily wired to respond to. Instruments like the theremin, violin, or bass clarinet are tools. But when a voice is distorted, layered, or used out of context, it bypasses logic and hits fear directly.